With reference to Mary Beard’s comments regarding Praxiteles’ ‘Aphrodite’ aired within episode two of the BBC series, Civilisations.

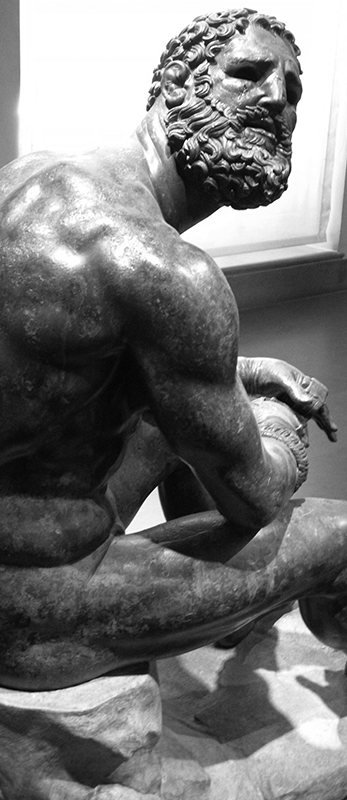

Initially, Mary references this bronze statue (below, ‘The Boxer At Rest’)…

… by saying

It’s the incisive brilliance of sculptures like the boxer that gives the impression that the Greek revolution was an unalloyed triumph of artistic achievement but there’s another way of looking at the Greek revolution and at its losses as well as its gains.

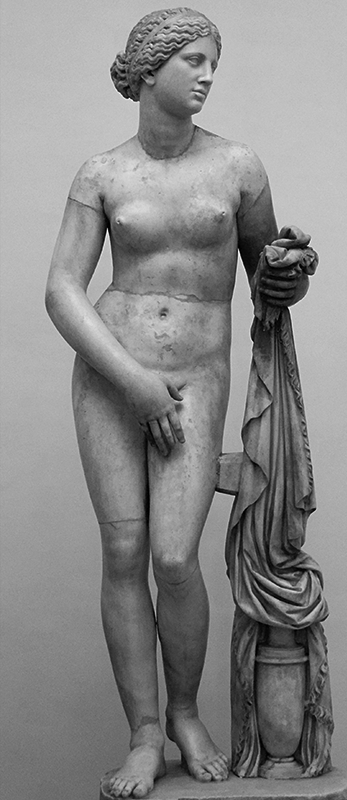

Mary then illustrates her continuing point further with reference to the Kore Phrasikleia of Ariston of Pylos (below)…

Remember Phrasikleia, who died unmarried?

She was made long before that revolutionary change.

What I love is her elegance and simplicity; the way she reaches out, offering a gift, or meeting us eye-to-eye.

That directness is exactly what gets lost in the Greek revolution. Later sculptures may be more supple than Phrasikleia. They may seem to move more adventurously but they don’t engage us in the same way. In fact, if you try to look them in the eye, many of them coyly avoid your gaze and many of them, like the boxer, seem lost in their own world.

It’s almost as if the involved viewer has become an admiring voyeur and we’re one step on the way to sculpture becoming an art object.

Now Phrasikleia is determinedly resisting being an art object and one thing she’s not is coy.

But the problems of the Greek revolution don’t stop here.

Just a few hundred years after Phrasikleia this is what female sculptures of the Greek world had become…

Mary then comments on this statue (above, the Menaphantos Aphrodite, in the pose form/variant known as Venus Pudica) as follows:

This sculpture exposes some of the dangers in the pursuit of realism and that blurry and perilous boundary between artefact and flesh.

This notorious body belongs to the Greek goddess Aphrodite.

It’s a Roman version of a ground-breaking statue by the sculptor Praxiteles in the 4th Century BC.

In the ancient world this was celebrated as a milestone in classical art because it was the first naked statue of a woman.

Today it’s difficult to see beyond the ubiquity of images like this and recapture just how daring and dangerous it would have been for the ancient Greeks.

This sculpture broke through social conventions. It wasn’t just that up to this point female statues had been clothed; in some parts of the Greek world real-life women (at least among the upper class) went around veiled.

But in fact it wasn’t just the nakedness, this Aphrodite broke the mould in a decidedly erotic way.

Just look at her hands. Are they modestly trying to cover herself up? Are they pointing us in the direction of what we want to see most? Or are they simply a tease?

Whatever the answer, Praxiteles has established that edgy relationship between a statue of a woman and an assumed male viewer that has never been lost from the history of european art.

But that difficult boundary between statue and flesh was understood by the Greeks themselves. They told a tale that shows how they too knew of the perils they faced when creating what they saw as realistic images of the human body.

One night it was said, a young man became so aroused by this statue he forced himself upon it leaving a stain of lust on her thigh. He later threw himself over a cliff to his death in shame.

That story of the stain not only shows how a female statue can drive a man mad but also how art can act as an alibi for what was, let’s face it, rape. Don’t forget Aphrodite never consented.

But however troubling the Greek revolution was in its own time there’s a deeper legacy that reaches the modern age. One to which we’re often blind. Inherited by ancient Rome, rekindled in the european renaissance, faith in the Greek version of realism persisted through time and as the reverence for the classical style grew it would be invested with even greater meaning. Not just as a model for figurative art to aspire to but nothing less than a barometer of civilisation itself.

Personal comment.

I am an ardent admirer of Mary’s work in print and on the small screen. Though I am familiar with her topics (having studied ancient and classical history for forty years or so), I find her contributions incredibly illuminating and delivered in an accessible and engaging manner rarely found amongst classicists. It is one of the sincere pleasures of my life to watch her marvellous spangled pumps meander around piles of oft-disregarded rocks and to immerse myself in her books, where her perceptive view of the classical world easily fosters new insight or a renewed thought or twelve in my frequently dusty brainpan.

‘How Do We Look‘ is an apt and interesting view to take within the context of a new ‘Civilisations’ series predated by Kenneth Clarke’s 1969 original personal view, especially in the (dated) context of Clarke’s ‘great man’ approach that (arguably) reduced the role of women to objects of inspiration or desire. Mary’s approach sits well alongside Berger’s ‘Ways of Seeing’ (which was itself (at times) a direct riposte of Clarke’s presentation) and Mary herself (seemingly) gives many a hefty nod to the feminist concept of the ‘male gaze.’

OK. So. Here’s my moanywhinewinge.

I would have preferred that Mary illustrated her segments with art that she actually (even passionately) admires; aspects of which she could illustrate positively in terms of whatever she believes ‘civilisation’ to be.

Much of the time, she appears to be either mildly disgusted toward many of the artefacts she has decided to show us, negative in her appraisals, or somewhat contrarian in her comments.

However, this is no more than a personal gripe and no foundation for serious criticism. I like Mary and enjoy the glimpses she gifts me of a world seen through her eyes, even if I hold a differing view on occasion.

It is in her appraisal of and comments regarding Praxiteles’ Aphrodite that I found myself inwardly wincing.

And here’s why.

First naked statue of a woman? Surely that should be first statue of a naked woman? Just a few hundred years? Just? We’ll get to the thorny issue of whether a statue can consent, later.

Mary is aware of the technical development involved from the earlier Kore/Kouros style (within which her admired Phrasikleia belongs) through to the work of Praxiteles (and others) which she rightly says is some four-hundred years later.

This is a huge topic upon which hundreds of books have been written and in no way can I do it justice here. In short, this technical and skill development is reflected in the ‘freeing’ of the human body from the marble such that heads could tilt, necks turn, and arms and legs could flow more ‘realistically’ away from the torso, often achieved through a developing understanding of mass and gravity and the ‘cheats’ that could be utilised to avoid fractures and breakages.

Ariston of Pylos did not have this level of skill or knowledge. Praxiteles did, at least to a greater, necessary degree. Which is not to reduce Phrasikleia in any way; she’s incredible.

The later ‘realism’ of Greek statuary is a direct consequence of the continual development of this skill and technical prowess and by ‘realism’ I refer to a wider range of human body movement and subsequent depth of expression (as an actual representation of what real humans can achieve) beyond that which could be achieved by Ariston.

How’s that for a tortured sentence?

For example. Ariston’s Phrasikleia demonstrates a development from earlier Kore styles in that Phrasikleia’s left arm is moved from the hip to the chest and her right arm is able to be separated slightly by using a cloth-grip (cheat) to support the marble of the arm. As such, Phrasikleia represents her own breakthrough on the journey to realism but there’s a way to go yet before the ‘Greek revolution.’

Praxiteles and others also utilised similar tricks to support marble (or bronze) mass (cloth drapes, tree trunks, amphorae etc).

I would argue that it is this ‘freeing’ of the human body from the marble that constitutes the fundamental achievement of the ‘Greek revolution’ and that the expression of ‘coyness’ or ‘seduction’ or ‘pathos’ or ‘erotic teasing’ or ‘dejection’ (etc) is a direct consequence.

The sum of technical skill, knowledge and emotional expression is why Praxiteles and his successors are considered to be so vital to ‘civilisation’ (whatever you may think this means). Realism in the form of a wider range of emotional expression was enabled through technical and skill development and acquisition. This is the ‘breakthrough’ of ‘classical’ statuary that stems from Greece, rather than from Egypt, China, India, Mesoamerica or Mesopotamia (and by this I do not mean or infer any disparaging denegration).

There is (of course) expression in earlier works (of many cultures) but much of it must often be implicit as the skills to make such expression explicit (in the sculpted human form) simply did not exist.

It is thanks to skill and a knowledge grounded in technical expertise (developed over centuries) alongside qualities of empathy and human understanding that the sculptor of ‘the boxer’ (for example) is actually able (in metal) to convey a sense that his subject might appear to be ‘lost in his own world.’

I might even suggest (for the sake of transient contemplation) that Ariston of Pylos would have gladly given a less-valued appendage to have been capable of imbuing his sculpture of Phrasikleia with more than elegance, simplicity and directness. Perhaps. Perhaps not. Besides, this does not intrude upon the subjective opinion and perception of any ‘viewer.’

The ‘merit’ of associated expression (particularly when connected to allure, eroticism, seduction etc) is grounded in subjectivity, which is as reflective of the viewer as of the intention of the artist (and is entirely relevant with regards to Mary’s topic in this episode). To me, this eventually boils down to matters of ‘taste’ which can (variously) be rebelliously individual or influenced by societal and cultural factors or pressure, say.

I do not seek to question Mary’s taste, whatsoever; she is wholly entitled to her subjective taste, as are we all. And even her rebellious individualism, too. Damned right.

But I do take issue with some aspects of her presentation and comments and with some aspects omitted.

For example, Mary could have shown a brief development of Kore-style statuary that led to Ariston’s Phrasikleia and mentioned, briefly, the aspects of skill and technical acquisition that linked her to Praxiteles’ later work. thus illustrating (a little) the path that led to the ‘Greek revolution.’

Mary could have mentioned that the copy-style of the particular Aphrodite she showcased (exclusively) was not the only copy-style adopted by later copyists. This one, for example…

… or this…

… both of which are arguably closer to Praxiteles’ original than the variant she chose to showcase as suggested in this coin from Cnidus, where the original statue was housed.

Of course variants other than the Aphrodite of Menophantos are arguably far less blatantly ‘erotic’ and certainly would not have allowed Mary to speculate as she does…

But in fact it wasn’t just the nakedness, this Aphrodite broke the mould in a decidedly erotic way.

Just look at her hands. Are they modestly trying to cover herself up? Are they pointing us in the direction of what we want to see most? Or are they simply a tease?

… or talk quite so persuasively about the

… dangers in the pursuit of realism and that blurry and perilous boundary between artefact and flesh.

Mary could have mentioned that Praxiteles (according to Pliny the Elder) created not just one but two statues of Aphrodite at the same time; one draped and one nude. Pliny tells us that the city of Kos bought the draped statue as they thought the nude to be indecent and that it would thus negatively reflect upon their city, and that the nude was bought by Cnidus which ultimately brought it fame. But this might have negated to a degree her comment that…

This sculpture broke through social conventions. It wasn’t just that up to this point female statues had been clothed; in some parts of the greek world real-life women (at least among the upper class) went around veiled.

I realise that all of this might be argued to be nit-picking (mea culpa), yet perhaps with as much validity as a claim that Mary was cherry-picking to illustrate her own, somewhat negative and seemingly disapproving 21st Century narrative concerning the veiling of ‘real-life women,’ for example.

Which things Mary fails to mention or draw attention to are as indicative of her narrative as those things she does mention or draw attention to, surely.

Which brings me to her inclusion of the ‘cautionary tale’ from Pseudo-Lucian’s Erotes, which, I must admit, almost made me facepalm and which caused me to watch and rewatch the segment in an attempt to understand her point.

One night it was said, a young man became so aroused by this statue he forced himself upon it leaving a stain of lust on her thigh. He later threw himself over a cliff to his death in shame.

That story of the stain not only shows how a female statue can drive a man mad but also how art can act as an alibi for what was, let’s face it, rape. Don’t forget Aphrodite never consented.

One pedantic point I must make here is that a human male cannot actually ‘rape’ a stone statue (whatever it depicts), even less so if the human male in question is the mere anonymous subject of a tale told by temple assistants for their own (pecuniary?) ends. ‘Forced himself?’ On what is that based? I mean… really.

Nor can this tale illustrate that art can serve as an ‘alibi for what was, let’s face it, rape.’ I mean… reallyreally.

Another (wholly pedantic) point is that there is no indication of ‘shame’ on behalf of the young man. He may well have thrown himself off the cliff in a fit of fulfilled ecstasy, for all we know. I mean… heck.

All of this seems to be painted with a brooooad brush saturated with inky feminismus (and yes, I just made that word up).

I could perhaps go so far as dismissing these comments as sensationalist hyperbolic narrative-driven nonsense, because Mary is basing them entirely on the tale from the Erotes, rather than the mere nakedness of the statue (that is referenced as some kind of subtle, yet rather seedy conflation) and is contorting the entire commentary and content to further a poorly-illustrated cautionary tale of her own, replete with soundtrack and lascivious edits.

After all, it’s not as though Mary is arguing that all nude depictions of a woman (even if sensuous, erotic or downright pornographic) can be ‘an alibi’ for rape and given that the ‘rape’ in the tale never happened in any realm of reality… why on earth anchor this ‘dangers of the male gaze’ argument so ludicrously?

Are we talking about the statue of Aphrodite (in an erotic copy-style entirely chosen to make her seemingly disapproving point) or ‘the stain’ (from a tale within a tale masquerading as an alibi for rape)… or that Aphrodite failed to give consent?

And how can we know that Aphrodite never consented? Is it because she was (in this tale) a statue that couldn’t speak because if that’s the reasoning then she couldn’t have been raped, either. Mary (necessarily) mixes descriptors inconsistently between ‘Aphrodite’ and ‘statue’ in keeping with her (for me) confused narrative and besides, we have no way of knowing what transpired between Aphrodite and the young man after the attendants unwittingly locked them into the temple together… alone… besides the presence of ‘the stain’ itself which appears to have been – in reality – a blemish in the original marble from which a gossipy myth developed.

Still… from all of this Mary concludes that the ‘Greek revolution’ was, and continues to be, troubling.

Really?

A complete reading of the Erotes might help clarify a few points and I have included much of this work, below, but I’m going to close with the following observations:

Not only was this a statue of a naked woman by a sculptor with the skill and technical expertise to portray the female body in a ‘realistic’ aspect, imbued with emotion and expressiveness… thus with a ‘power’ in and of itself… but it was a statue of the Goddess Aphrodite and housed within her temple precinct.

Aphrodite was not an ordinary woman to the Greeks of this period; she was a goddess (and for many, no less ‘real’ because of that)… representing love and beauty, eroticism, desire, pleasure, sensuality, fertility and procreation, prostitution and in her earlier iterations she was a war-goddess as well as being described as Melainis and Homonoia… and was worshipped and adored by women as well as men. That was a great deal for Praxiteles to sculpt into his marble Aphrodite beyond what a Greek might arguably think of (merely) as a naked female.

Greeks came to her temples in part to worship her various representations and where the ‘spirit’ or ‘essence’ or ‘divinity’ of the goddess – or even the actual goddess herself – could be felt or glimpsed. For the Greeks, statues representing deities were not mere stone or bronze; they were vessels for the divinity and as such, capable of animation, agency and expression (both physical and emotional).

The ‘young man of a not undistinguished family — though his deed has caused him to be left nameless — who often visited the precinct, was so ill-starred as to fall in love with the goddess.’

In short, from the perspective of the young man (and any other contemporary) this was no mere statue and the nakedness of the statue (no matter how ‘teasingly erotic’) wholly insufficient to cause the man to ‘rape’ it.

It was the goddess Aphrodite with whom the ‘young man’ fell in love, not the statue.

For all we know, Aphrodite ‘possessed’ the statue, appeared in person, or the young man was glamoured by the naked Aphrodite through her statue which would make him the victim of the encounter, rather than the perpetrator; such an interpretation would be in keeping with the accounts of interactions between gods, goddesses and mortals and the Erotes account could certainly be interpreted that way; the tale of ‘the stain’ is given far less space than the resultant discussion as to what it may mean or illustrate. The Erotes goes on to discuss the tale further (and with more (homo-erotic) nuance) than the ‘stain’ Mary draws attention to, giving far more insight than questions of ‘rape’ or ‘consent’ which are themselves (perhaps) issues linked to and reflective of our own modern times.

The tale was told by temple attendants with (perhaps) a motive similar to that of the attendants at Delphi (say), or those found at the temples of Hera, Zeus, Athena and so on, where illustrative tales of prophecy, strength in arms, wisdom (or whatever had relevance) would be heard; tales intended to create wonder and amazement and promote the deity beyond the confines of the temple itself and thus bring in the punters.

This tale is representative (I might argue) not as a metaphor of the understanding held by the Greeks themselves of the ‘difficult boundary between statue and flesh’ but illustrative (in a contemporary sense) of the power of Aphrodite herself.

I don’t believe this tale to be representative of a ‘Greek’ realisation of the dangers of the naked (even eroticised) female statue form (many other things arguably are, they’re just not mentioned by Mary).

An argument for the ‘troubling’ ‘truth’ of the ‘Greek revolution’ based almost in revisionist kyriarchal concepts (which has some merit as a topic for discussion, perhaps) is not one I myself would have included in this series but in content, context and delivery on this issue, Mary made me wince and (almost) facepalm.

So what, I hear you say. And I couldn’t agree more.

I’ll get over it.

Note:

The episode in which this segment is embedded was first broadcast in the UK on International Women’s Day (March 8th) and Mary has written a book to accompany her two-episode contribution (to the nine-episode series) entitled ‘How Do We Look / The Eye of Faith’ which is being publicised alongside her earlier work ‘Women and Power.’ Perhaps Mary is expressing an ideology reflective of our time more akin to the feminist concept of the ‘male gaze’ than that proffered by Berger and more recent art historians.

What I do find troubling is a reappraisal of the past undertaken through an ideological lens and/or subsumed beneath a covert (yet overtly-hefty) daub of contemporary identity-politics-laden beige.

Pseudo-Lucian : Affairs of the Heart (11-19)

- Now, as we had decided to anchor at Cnidus to see the temple of Aphrodite, which is famed as possessing the most truly lovely example of Praxiteles’ skill, we gently approached the land with the goddess herself, I believe, escorting our ship with smooth calm waters. The others occupied themselves with the usual preparations, but I took the two authorities on love, one on either side of me, and went round Cnidus, finding no little amusement in the wanton products of the potters, for I remembered I was in Aphrodite’s city. First we went round the porticos of Sostratus and everywhere else that could give us pleasure and then we walked to the temple of Aphrodite. Charicles and I did so very eagerly, but Callicratidas was reluctant because he was going to see something female, and would have preferred, I imagine, to have had Eros of Thespiae instead of Aphrodite of Cnidus.

- And immediately, it seemed, there breathed upon us from the sacred precinct itself breezes fraught with love. For the uncovered court was not for the most part paved with smooth slabs of stone to form an unproductive area but, as was to be expected in Aphrodite’s temple, was all of it prolific with garden fruits. These trees, luxuriant far and wide with fresh green leaves, roofed in the air around them. But more than all others flourished the berry-laden myrtle growing luxuriantly beside its mistress and all the other trees that are endowed with beauty. Though they were old in years they were not withered or faded but, still in their youthful prime, swelled with fresh sprays. Intermingled with these were trees that were unproductive except for having beauty for their fruit-cypresses and planes that towered to the heavens and with them Daphne, who deserted from Aphrodite and fled from that goddess long ago. But around every tree crept and twined the ivy, devotee of love. Rich vines were hung with their thick clusters of grapes. For Aphrodite is more delightful when accompanied by Dionysus and the gifts of each are sweeter if blended together, but, should they be parted from each other, they afford less pleasure. Under the particularly shady trees were joyous couches for those who wished to feast themselves there. These were occasionally visited by a few folk of breeding, but all the city rabble flocked there on holidays and paid true homage to Aphrodite.

- When the plants had given us pleasure enough, we entered the temple. In the midst thereof sits the goddess — she’s a most beautiful statue of Parian marble — arrogantly smiling a little as a grin parts her lips. Draped by no garment, all her beauty is uncovered and revealed, except in so far as she unobtrusively uses one hand to hide her private parts. So great was the power of the craftsman’s art that the hard unyielding marble did justice to every limb. Charicles at any rate raised a mad distracted cry and exclaimed, “Happiest indeed of the gods was Ares, who suffered chains because of her!” And, as he spoke, he ran up and, stretching out his neck as far as he could, started to kiss the goddess with importunate lips. Callicratidas stood by in silence with amazement in his heart. The temple had a door on both sides for the benefit of those also who wish to have a good view of the goddess from behind, so that no part of her be left unadmired. It’s easy therefore for people to enter by the other door and survey the beauty of her back.

- And so we decided to see all of the goddess and went round to the back of the precinct. Then, when the door had been opened by the woman responsible for keeping the keys, we were filled with an immediate wonder for the beauty we beheld. The Athenian who had been so impassive an observer a minute before, upon inspecting those parts of the goddess which recommend a boy, suddenly raised a shout far more frenzied than that of Charicles. “Heracles!” he exclaimed, “what a well-proportioned back! What generous flanks she has! How satisfying an armful to embrace! How delicately moulded the flesh on the buttocks, neither too thin and close to the bone, nor yet revealing too great an expanse of fat! And as for those precious parts sealed in on either side by the hips, how inexpressibly sweetly they smile! How perfect the proportions of the thighs and the shins as they stretch down in a straight line to the feet! So that’s what Ganymede looks like as he pours out the nectar in heaven for Zeus and makes it taste sweeter. For I’d never have taken the cup from Hebe if she served me.” While Callicratidas was shouting this under the spell of the goddess, Charicles in the excess of his admiration stood almost petrified, though his emotions showed in the melting tears trickling from his eyes.

- When we could admire no more, we noticed a mark on one thigh like a stain on a dress; the unsightliness of this was shown up by the brightness of the marble everywhere else. I therefore, hazarding a plausible guess about the truth of the matter, supposed that what we saw was a natural defect in the marble. For even such things as these are subject to accident and many potential masterpieces of beauty are thwarted by bad luck. And so, thinking the black mark to be a natural blemish, I found in this too cause to admire Praxiteles for having hidden what was unsightly in the marble in the parts less able to be examined closely. But the attendant woman who was standing near us told us a strange, incredible story. For she said that a young man of a not undistinguished family — though his deed has caused him to be left nameless — who often visited the precinct, was so ill-starred as to fall in love with the goddess. He would spend all day in the temple and at first gave the impression of pious awe. For in the morning he would leave his bed long before dawn to go to the temple and only return home reluctantly after sunset. All day long would he sit facing the goddess with his eyes fixed uninterruptedly upon her, whispering indistinctly and carrying on a lover’s complaints in secret conversation.

- But when he wished to give himself some little comfort from his suffering, after first addressing the goddess, he would count out on the table four knuckle-bones of a Libyan gazelle and take a gamble on his expectations. If he made a successful throw and particularly if ever he was blessed with the throw named after the goddess herself, and no dice showed the same face, he would prostrate himself before the goddess, thinking he would gain his desire. But, if as usually happens he made an indifferent throw on to his table, and the dice revealed an unpropitious result, he would curse all Cnidus and show utter dejection as if at an irremediable disaster; but a minute later he would snatch up the dice and try to cure by another throw his earlier lack of success. But presently, as his passion grew more inflamed, every wall came to be inscribed with his messages and the bark of every tender tree told of fair Aphrodite. Praxiteles was honoured by him as much as Zeus and every beautiful treasure that his home guarded was offered to the goddess. In the end the violent tension of his desires turned to desperation and he found in audacity a procurer for his lusts. For, when the sun was now sinking to its setting, quietly and unnoticed by those present, he slipped in behind the door and, standing invisible in the inmost part of the chamber, he kept still, hardly even breathing. When the attendants closed the door from the outside in the normal way, this new Anchises was locked in. But why do I chatter on and tell you in every detail the reckless deed of that unmentionable night? These marks of his amorous embraces were seen after day came and the goddess had that blemish to prove what she’d suffered. The youth concerned is said, according to the popular story told, to have hurled himself over a cliff or down into the waves of the sea and to have vanished utterly.

- While the temple-woman was recounting this, Charicles interrupted her account with a shout and said, “Women therefore inspire love even when made of stone. But what would have happened if we had seen such beauty alive and breathing? Would not that single night have been valued as highly as the sceptre of Zeus?” But Callicratidas smiled and said, “We don’t know as yet, Charicles, whether we won’t hear many stories of this sort when we come to Thespiae. Even now in this we have a clear proof of the truth about the Aphrodite whom you hold in such esteem.” When Charicles asked how this was, I thought Callicratidas made a very convincing reply. For he said that, although the love-struck youth had seized the chance to enjoy a whole uninterrupted night and had complete liberty to glut his passion, he nevertheless made love to the marble as though to a boy, because, I’m sure, he didn’t want to be confronted by the female parts. This occasioned much snarling argument, till I put an end to the confusion and uproar by saying, “Friends, you must keep to orderly enquiry, as is the proper habit of educated people. You must therefore make an end of this disorderly, inconclusive contentiousness and each in turn exert yourself to defend your own opinion; for it’s not yet the time to leave for the ship, and we must employ that free time for enjoyment and also for such serious matters as can combine pleasure and profit. Therefore let us leave the temple, since great numbers of the pious are coming in, and let us turn aside into one of the feasting-places, so that we can have peace and quiet to hear and to say whatever we wish. But remember that he who is vanquished will never again vex our ears on similar topics.”

- This suggestion of mine pleased them and after they had agreed to it we left the temple. I was enjoying myself as I was weighed down by no cares, but they were rolling mighty cogitations up and down in their thoughts, as though they were about to compete for the leading place in the processions at Plataea. When we had come to a thickly shaded spot that afforded relief for the summer heat, I said, “This is a pleasant place, for the cicadas chirp melodiously overhead.” Then I sat down between them in right judicial manner, bearing on my brows all the gravity of the Heliaea itself. When I had suggested to them that I should draw lots to decide who should speak first, and Charicles had drawn this privilege, I bade him begin the debate at once.

- He rubbed his brow lightly with his hand and after a short pause began as follows: “To you, Aphrodite, my queen, do my prayers appeal to give help in my advocacy of your cause. For every enterprise attains complete perfection if you shed on it but the faintest degree of the arts of persuasion that are your very own; but discourses on love have particular need of you. For you are their only true mother. Come, you who are the most feminine of all, plead the cause of womankind, and of your grace allow men to remain male, as they were born to be. Therefore do I at the very outset of my discourse call as witness to back my plea the first mother and earliest root of every creature, that sacred origin of all things, I mean, who in the beginning established earth, air, fire and water, the elements of the universe, and, by blending these with each other, brought to life everything that has breath. Knowing that we are something created from perishable matter and that the life-time assigned each of us by fate is but short, she contrived that the death of one thing should be the birth of another and meted out fresh births to compensate for what dies, so that by replacing one another we live for ever. But, since it was impossible for anything to be born from but a single source, she devised in each species two types. For she allowed males as their peculiar privilege to ejaculate semen, and made females to be a vessel as it were for the reception of seed, and, imbuing both sexes with a common desire, she linked them to each other, ordaining as a sacred law of necessity that each should retain its own nature and that neither should the female grow unnaturally masculine nor the male be unbecomingly soft. For this reason the intercourse of men with women has till this day preserved the life of men by an undying succession, and no man can boast he is the son only of a man; no, people pay equal homage to their mother and to their father, and all honours are still retained equally by these two revered names.